THE SCIENCE OF SKIN

The skin is one of the largest organs in the body in surface area and weight. An understanding of skin biology and structure helps showcase how nutrition plays a pivotal role in skin health.

The skin is one of the largest organs in the body in surface area and weight. An understanding of skin biology and structure helps showcase how nutrition plays a pivotal role in skin health.

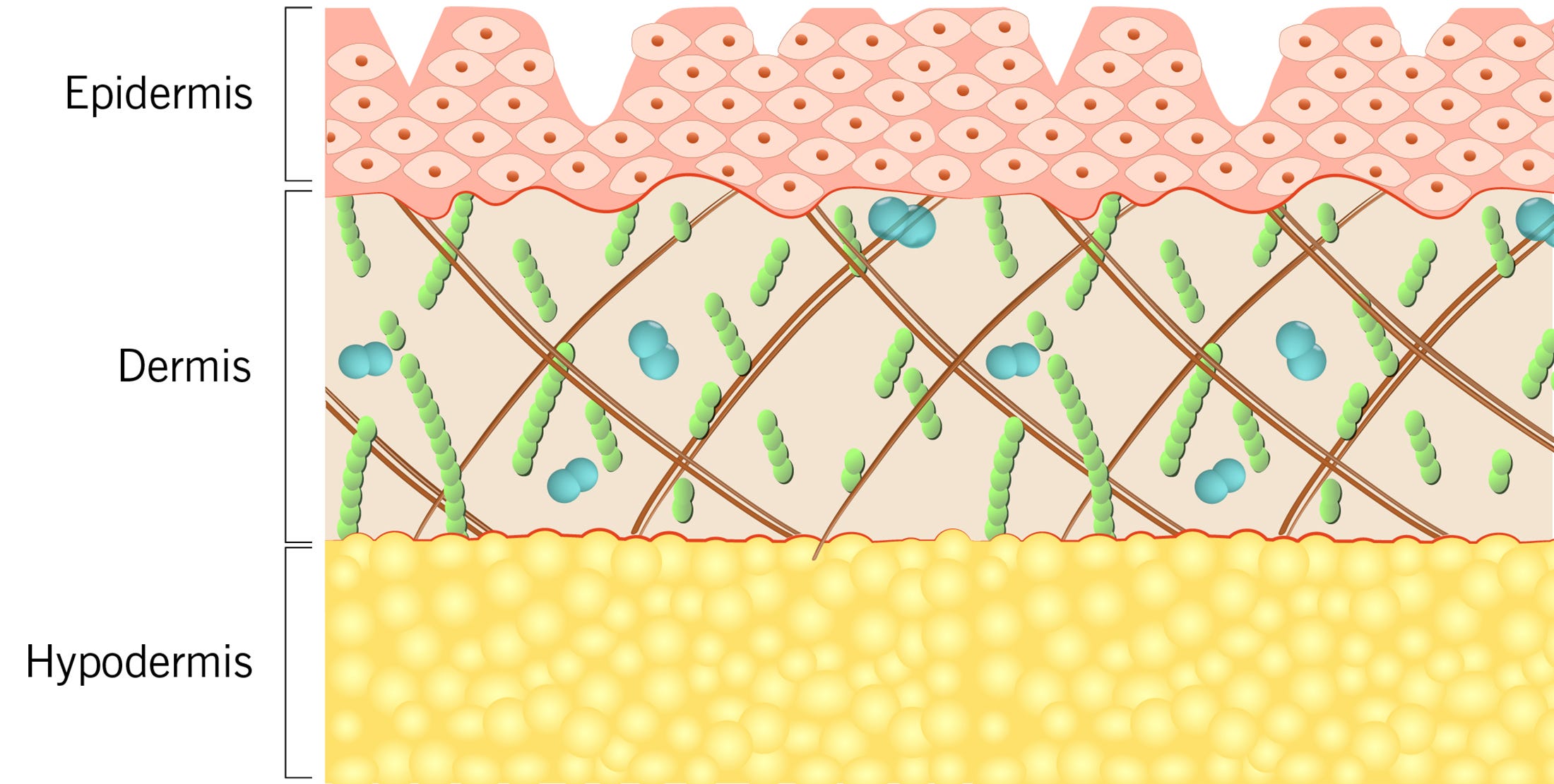

The epidermis is the relatively thin, tough and outer layer of the skin. The epidermis (along with other layers of the skin) protects the internal organs, muscles, blood vessels and nerves against trauma.

In contrast, the dermis is a thick layer of fibrous and elastic tissue (made mostly of collagen, with a small but important component of elastin) which gives the skin its flexibility and strength. The dermis contains nerve endings, sweat glands and oil (sebaceous) glands, hair follicles and blood vessels.

Below the dermis lies a layer of fat that helps insulate the body from heat and cold, provides protective padding and serves as an energy storage area. The fat is contained in living cells, called fat cells, help together by fibrous tissue.

The primary function of the skin is to act as a protective barrier. The skin keeps vital chemical and nutrients in the body while providing a barrier against dangerous substances from entering the body. It also provides a shield from the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation emitted by the sun.

The skin is an organ of regulation. The skin regulates several aspects of physiology including: body temperature via sweat and hair, and changes in peripheral circulation and fluid balance via sweat. It also acts as a reservoir for the synthesis called vitamin D.

The skin is an organ of sensation. The skin contains an extensive network of nerve cells that detect and relay changes in the environment. There are separate receptors for heat, cold, touch and pain.